- Home

- Nancy Campbell

The Library of Ice Page 2

The Library of Ice Read online

Page 2

The ice, always mutable, is now dangerously unpredictable. During one of his many visits to the museum, Peter tells me that for the last few winters there has scarcely been sufficient ice for him to leave the island on his sled. Other times there’s too much snow: he must take along a shovel to clear the way to his fishing nets. No wonder he has so much time for coffee! He is pessimistic about the future. His beloved dogs are restless. Without their regular sled journeys over the sea ice, they are getting no exercise. Hunters cannot afford to feed animals that do not work, and he knows men who have been forced to shoot their dogs.

In an attempt to comprehend the changing way of life and presence of death on Upernavik, I turn to the bookshelves in the museum. There’s not much available. Most of the books are pictorial or practical: photograph albums and manuals on how to build a kayak or carve a paddle. I browse through a Greenlandic–English dictionary from the 1920s, not looking for any words in particular but rather letting chance definitions catch my eye. I discover that ilissivik means ‘bookshelf’ while ilisissuppaa means merely ‘a shelf or cupboard’. A subtle difference. They are clearly related to the verb illisivit, listed further up the page, meaning ‘to put it away’. And for those with too many shelves and bookcases, the dictionary informs me that ilisiveeruppaa is the verb for ‘having put something in a safe place but being unable to find it again’. I begin to see why this culture feels ambivalent about the printed word.

In an old newspaper I find an obituary of Simon Simonsen, a famous hunter from Upernavik, whose sons followed his profession. A tribute to his skills concludes: ‘And if the sun had not erased the tracks upon the ice, they would tell us of polar bears and the man who had the luck to catch bears.’ It dawns on me that tracks on the ice are considered a better way of telling hunting stories than any words. Even their disappearance is part of the story – an indication of time passing, as the hunter and hunted move on. When the last of the ice has melted, I realize, the records of the past will be the least of our concerns.

As January rolls into February the skies begin to grow lighter. Behind the high mountains the sun is returning. A few miles to the north, glaciers churn their way through the basalt cliffs and thunder into the icefjord. With each new day these icebergs drift slightly further south and crumble a little more into the water. These scarcely perceptible changes are just enough to suggest, disquietingly, that icebergs might be living things with minds of their own. In silhouette, the varied forms – domes and pinnacles, and a few great tabular bergs – look like a line of writing. I feel I might understand what it said, if I looked long enough.

Grethe is pleased I am taking an interest in the environment beyond the museum. It’s what she has been secretly hoping for, I know. She finds my obsession with objects, with books, with typing, curious and a little unhealthy. Every day I walk down to the shore and make a short film at the same spot. I hold my breath as I record the ice, trying to hold the camera still for as long as possible in my clumsy gloves. The ice here is uncanny, having been broken down by tides and storms, and reformed by cold, like Japanese porcelain repaired by a kintsugi master with a seam of silver lacquer. The view through the lens is always different. Sometimes water trickles over channels in the melting ice, which gently rises and falls with the incoming tide. On other days a thick rind of ice covers the sea, or a blizzard obscures everything. The shore-fast ice creeps across the bay, extending the shoreline by a mile and more, only to vanish on a stormy night. Making the film is a means to encourage my own close looking – but it’s hard to see the boundaries of an object when I don’t have words for what I’m seeing. Where does one ice formation end and another begin?

As the brief daylight fades, I return indoors. I relish the terms I find in an online oceanographic dictionary: frazil ice describes fine spicules and plates of ice suspended in water; nilas, the thin elastic crust that bends with waves and swell, and grows in a pattern of interlocking fingers; and easiest of all to spot, pancake ice, those irregular circular shapes with raised rims where one ‘pancake’ has struck against another.

When I’d been filming for a couple of weeks, it was time for a new vantage point. I dared myself to take a few steps out onto the shore-fast ice, like the fishermen I’d watched. I stepped gingerly, all too aware of the ocean just inches under my feet. I hoped that by standing upon the ice I’d achieve some kinship with the islanders. As I tiptoed back again, Grethe came down to the shore to meet me, and I wondered if she was going to reprimand me for my risky behaviour. But she was laughing. A little hurt, I asked her why.

‘Because you have been walking on the ice all this time,’ she said, pointing to the snow we stood upon, which I had assumed covered a rocky shore.

Ice does not always look like ice. I think of the origin myth, of the time when ice could burn. In those days, people had powerful words that when spoken could transport the speaker – home and all – to places where they could settle and find food. The saying of the words brought the place into existence. I wondered what words might have the power to carry people to a place of safety today?

Grethe taught me to say, ‘Illilli!’ when I passed her a cup of coffee, ‘There you go!’ She told me proudly that now I could be identified as coming from Upernavik: ‘If you were from Ilulissat, you’d say illillu.’

It was flattering to think I was becoming part of the community, but I was all too often reminded of my difference.

‘You work too hard,’ Grethe said one day. ‘You should be careful or you will never get a husband.’

It wasn’t the future husband I was concerned about so much as my existing friendships. Grethe kept a close eye on how often I plugged the ethernet cable into my laptop. Connectivity in Greenland is expensive, sporadic and slow. I treasured the letters that made it to me in a mail sack in the front seat of the plane, and even occasional parcels: the box of spices which my friend Ruth bagged up and labelled – turmeric, ginger, coriander – bringing scents of London to my rudimentary kitchen cupboard. The hand-printed poster that Roni, a former colleague, sent from Manhattan, which featured a quote from Gertrude Stein’s ‘Valentine for Sherwood Anderson’: ‘If they tear a hunter through, if they tear through a hunter, if they tear through a hunt and a hunter . . .’ I ran my fingers over the unmistakable deep bite of metal type on the luxuriant paper.

One night, after a quick supper of fish fingers, I take the book of Danish fairy tales down from the shelf and curl up on the sofa to read the story of the Snow Queen again. Like many fairy tales, it’s disturbing: it deals with an abducted child, whose eyes and heart have been pierced by shards of glass from a goblin’s broken mirror. I empathize with Kay, imprisoned by his regal kidnapper in a great northern castle formed from over a hundred halls of drifting snow, enduring her ice-cold kisses and trying to make sense of his situation by writing new words in the sharp, flat pieces of ice she has given him to play with. The Snow Queen tells Kay that when he can form the word ‘eternity’, he will be his own master; she will give him the whole world – and a new pair of skates. Kay drags the ice around, composes many figures, forms different words, but he can’t manage to make the word ‘eternity’, however hard he tries.

When I first read this story years ago, I longed to travel with Kay on his dizzying sledge-ride to Spitsbergen, and I fell in love with the wayward robber girl – a minor character, but not to me. Andersen’s words have a different meaning for me now. I read on, stretching my feet out on the polar bear rug. ‘I must hasten away to warmer countries,’ says the Snow Queen. ‘I will go and look into the black craters of the tops of the burning mountains, Etna and Vesuvius. I shall make them look white, which will be good for them, and for the lemons and the grapes.’ Away she flies, leaving Kay alone in her castle. And there his friend Gerda finds him, still looking at his pieces of ice, thinking so deeply, and sitting so still, that anyone might suppose he was frozen. It is Gerda’s tears that wash the piece of enchanted glass from his eye, and set them both free.

The sun appeared for the first time on Valentine’s Day. A golden line split the mist above the snowy peaks, rested there for a moment, and then slipped away. I expected it to rise a grudging inch each day, but the days lengthened with bewildering speed. By March the darkness was just a memory, and I grew as complacent about sunlight as I had been about snow. I found I could go outside without wearing two pairs of gloves. The ice surrounding Upernavik began to fragment, and down by the shore the creaking of floes was replaced by the more harmonious sound of water trickling over stones. I was ready to fly south too, eager for luxuries like lemons and grapes again.

‘Why don’t you change your flight?’ Grethe asked. ‘You could stay another month, come with me on the motorboat to the settlements.’

I was tempted – but I knew that if I stayed another week I’d never leave. Besides, the book that was beginning to take shape in my mind as a gift for the museum required more than the laptop I was equipped with. I would need a printing press, and gouache paint, and perhaps a particular ‘velvet’ paper made by a mill on the River Axe in Somerset. I knew where I could find the press, and hospitality while I set the type. I boarded the plane as planned, leaving Upernavik to enjoy its springtime. The warm weather was coming, and archaeologists would arrive in the archipelago hoping to discover new objects to place in the museum while I was making mine. The tiny plane accelerated down the runway, and the pilot lifted its nose towards the sun. As the plane banked, the island seemed to tilt away from me. I looked over the ice floes tessellated upon the ocean like Kay’s puzzle. I wasn’t going to try spelling out eternity. There was not enough time left for that. The ice was beginning to disappear – and before it vanished I wanted to learn what words it would teach me.

I

SCIENTISTS

CALLING TIME

Bodleian Library, Oxford

Halley VI Research Station, Antarctica

But we need the books that affect us like a disaster, that grieve us deeply, like the death of someone we loved more than ourselves, like being banished into forests far from everyone, like a suicide.

Franz Kafka, letter to Oskar Pollak

I

A few months after returning from the Arctic, I sit at a wooden bay in the Upper Reading Room. Beyond the leaded glass windows the afternoon sky is indistinct. The forecast was bad this morning: rain is on the way. The clouds hanging over the spires of All Souls’ are such a static shade of white that the Gothic building looks like a cardboard cut-out stuck on a sheet of paper. The weather vane, a cast-iron arrow decorated with the initials of the compass points, doesn’t move.

My view is interrupted by decorative rosettes set within the window panes. They show human figures in sacred and secular pursuits: praying, tending animals, drawing water. Sundials used to be made this way, glass roundels hung against a window, painted with lines through which the light fell. You looked out of the window to tell the time.

The old glass distorts the view, as though it is raining already, as though the glass is running with water. Some students zip up their laptop cases and leave for lunch.

While spring returns I have been revisiting Upernavik in my mind: refining my sketches of icebergs, mixing inks to evoke the colour of the skies. I can’t forget the museum’s proviso and try to tell the story of ice using as few words as possible. The studio I have borrowed is still under construction, with walls on only three sides and a tarpaulin for a roof, but the printing press and drawers of metal type are already in place. I crank the cylinder forwards and backwards to print each page while builders drill into the walls beside me. Their radio plays classic love songs and breaking traffic reports. Not the usual conditions for fine press work, but within a few weeks I have managed to complete the book I will send back to Upernavik for the museum’s collection.

Rather than bringing my investigations to a close, this new publication just marks their beginning. My curiosity is growing. Living in the Arctic suggested new ways of thinking about language and landscape and time, but I want to ground these ideas. An appreciation of science would deepen my understanding of the ice formations I saw around Upernavik, and how they are changing. As I browse the entries in the library catalogue, I admire the informative records: each one is a book in miniature, composed by an anonymous author. A long list of fields: Title; Author; Publisher; Publication date; Format; Language; Identifier; Subjects; Aleph system number; Miscellaneous notes; Call number. A code for every book that has ever been printed in England, whether it is likely to find a reader or not. A register to bring order to this vast collection of information, buried in vaults beneath the ancient building.

I order The White Planet from the stacks. On the book jacket is a photograph of a stark icescape. The credit on the back flap tells me it is Fox Glacier on New Zealand’s South Island, the other side of the globe from Upernavik. The frozen sea looks violent, and somehow invites violence. I think of Kafka, who said that a book must unleash something painful, a terrible knowledge, it must ‘shake us awake’.

The book has been translated almost seamlessly from the original French. There are only a few places where the word choice makes me furrow my brow. I need to read quickly – I got to the library late this morning after a hairdresser’s appointment. I usually book in for a trim every six weeks or so, as soon as my short cut begins to grow out. While I was in Greenland, my style ran to seed. I am reassured now by the dull ritual: the hairdresser’s scissors orbiting my skull, snipping away the excess. More and more grey hairs these days, she points out, hoping I will book for a colour.

I shake my head, feeling how light it is. Tiny clippings fall onto the page as I read, and lie in the gutter of the book until I blow them away.

‘But we need the books . . .’ I begin to type the words that I will quote at the opening of this chapter. They precede Kafka’s more famous statement, ‘A book must be the axe for the frozen sea inside us.’ I type that too, and then I pause. Am I alone in liking the idea of possession by a frozen sea, more than that of the axe that would release the water? I doubt it: surely that is why the metaphor has become so famous. I let the cursor run back and delete it. I’m sure Kafka – who requested that his diaries and letters be burnt unread after his death – would understand.

The White Planet mentions ice cores, and I want to see an image. Online, I find a short documentary film that I watch with the sound off so as not to disturb the remaining researchers. I read the subtitles.

Dr Nerilie Abram is talking about her work with the British Antarctic Survey, analysing ice cores in order to understand past climates and predict those of the future. She has about two minutes to explain the complex science behind her research to a lay viewer.

The opening shot shows Dr Abram holding a circle of ice cut from a core. For a moment she is completely still; she looks like a painted saint in an icon, or a Roman emperor with an orbis terrarum, the symbol of one who holds the Earth – and all earthly power – in their hands. Until she blinks. She’s wearing a bright red waterproof; it’s the same colour as the expedition tents huddled on the Antarctic ice cap, which are already covered with a thin layer of snow. The colour of her jacket bleeds through the thin cross-section of ice, which is laced with tiny air bubbles. Disposed to find patterns, my eyes join up the bubbles. Now the ice appears to contain a hedgerow flower – cow parsley perhaps, or Queen Anne’s lace. Dr Abram holds the disc with as much anticipation as a child might hold a snow globe, but no amount of shaking will disrupt this snow scene.

When I was a child I longed to possess a paperweight I’d once seen, a dome of glass in which a dandelion clock was trapped. I used to pick dandelion clocks in the garden and blow away the seeds with their fine hairs. I never really believed that the number of puffs was a way to tell the time. Weren’t they more likely to indicate the power of my breath, like the tube the doctor made me blow into to test my lung capacity? Maybe the dandelion clocks would tell me the time I had left? But this dandelion was perfect and preserved under g

lass for ever. It would not grow, or wither, or let its seeds fall. It would place me outside of time.

Dandelions, cow parsley, Queen Anne’s lace: such plants are unknown in the Antarctic where this ice was found. The camera zooms in. Without Dr Abram’s fingers in the frame to set the scale, the disc could be as small as a communion wafer or large as a planet.

An aerial view of the Antarctic appears on the screen. That familiar irregular circle. Its neat circumference is interrupted by a scrawny peninsula jutting out into the ocean, looking for all the world as if it had been sketched by Dr Seuss. The continent’s circular appearance is down to the ice shelves that form three-quarters of the coastline, covering the many bays and inlets. Some of these shelves have begun to disintegrate; from the air you can see places where the ocean’s dark eclipse curves in towards the ice cap.

Antarctic ice shelves disperse in many ways. Bergs calve from the ice front, ice melts into the ocean beneath the shelf and drifting winds erode the surface. But the snow that falls on the central ice cap does not melt away. Each winter’s snowflakes are buried beneath further snowfalls. Over millennia, these layers compress and form firn, a grainy substance that contains pockets of atmospheric gases and even solid matter: infinitesimal specks of dust, ash and radioactive particles. Deep in the ice, the firn is pressed thinner. In the tiny spaces between the snowflakes, evidence remains of the environmental conditions at the moment they fell.

On research stations across the Antarctic ice cap – Halley VI, Dome F, Lake Vida, Vostok – scientists have begun to send drills down thousands of metres to extract cylinders of this ancient ice. Dr Abram reads a tracking device; she judges the click-click of depth readings and makes pencil notes. Her hands are gloved (red again) to protect them from the sub-zero temperatures. The great drill is winched lower. A core of ice is extracted and placed in a trough where it will be marked at intervals, and then cut along the marks with a rotary saw. Once a section has been sliced and stored in cold chambers dug out beneath the ice cap, another one will be drilled.

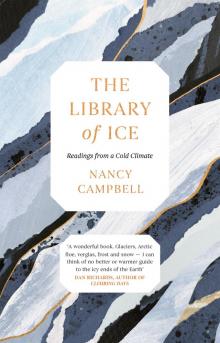

The Library of Ice

The Library of Ice